Terence M. Green interview from 1988

by Rob - April 28th, 2013.Filed under: Canadian SF, Fitzhenry.

Twenty-five years ago this month, the April 1988 issue of the late, lamented magazine Books in Canada published this interview by me (Robert J. Sawyer) with Toronto science-fiction writer Terence M. Green, then a high-school English teacher and now a lecturer in creative writing at Western University in London, Ontario.

Green writes wonderful novels, two of which were World Fantasy Award finalists. I reprinted his Children of the Rainbow, referenced below, in a slightly updated form as Sailing Times Ocean under my Robert J. Sawyer Books imprint from Fitzhenry & Whiteside.

Sailing Times Ocean is still in print, and other books by Terry have been reissued by Arc Manor’s Phoenix Pick line and from Richard Curtis’s E-Reads. You can find out more about those editions and what Terry is up to today on his blog.

And here’s that interview again, a quarter of a century later — an intriguing piece of Canadian science-fiction history:

Terence M. Green is quietly becoming Canada’s best science fiction writer. His first book, The Woman Who is the Midnight Wind (Pottersfield Press, 1987) collected his angst-filled short stories from Aurora: New Canadian Writings, Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine, and The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. St. Martin’s Press has just released his first novel in hardcover. Barking Dogs is a police thriller set in a near-future Toronto where infallible lie detectors — Barking Dogs — are everywhere. He recently completed another novel, Children of the Rainbow, a time-travel tale juxtaposing an Incan religious revival, Mutiny on the Bounty, and the anti-nuclear efforts of Greenpeace.

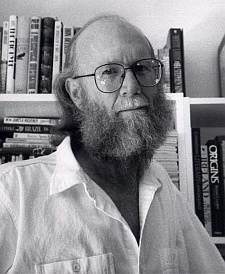

Terry Green was born in Toronto in 1947. He has a B.A. and a B.Ed. from the University of Toronto and an M.A. in Anglo-Irish Studies from University College, Dublin. He teaches high-school English at East York Collegiate Institute in Toronto and is the father of two boys. Green spoke about his life and work with journalist Robert J. Sawyer:

Robert J. Sawyer: Your first novel, Barking Dogs, is a violent work in the popular-fiction mold. Your second, Children of the Rainbow, is a more cerebral, literary book. It’s almost as if they were written by two different people.

Terence M. Green: For Barking Dogs, I studied what makes popular commercial fiction work and I consciously set out to include those elements. Since it was a first novel, I wanted to be sure it would sell. I wrote the second novel without those constraints. Each book satisfies different things in me, and I think they will satisfy different audiences. Am I two different people? I think everybody is many people. When I do my third novel, you will meet yet another Terry Green.

Sawyer: The main character of Barking Dogs, Police Officer Helwig, takes the law into his own hands. Is this book a call for urban vigilantism?

Green: No, but unfortunately a lot of people will read it that way and I’ll take a lot of criticism for it. If people read the book the way I intended it, they will see that it’s not a call for anything. Rather, it presents a new situation — a world in which the cop on the beat can know beyond a shadow of a doubt whether the person he is arresting is guilty. All I’m asking is for people to think about that.

Sawyer: So the theme of Barking Dogs is truth?

Green: Yes. I’ve always been intrigued by the degree to which we need to or should tell the truth. The job of the fiction writer is to tell the truth, but the job of so many people in the world — politicians, for instance — is not to. As a writer, I’ve always been interested in how you find the truth, how you deal with it. Truth is the crux of personal relationships; it’s what we all want to discover.

Sawyer: How did you go from that abstract philosophy to the concrete vision of a world full of hand-held lie detectors?

Green: I realized that legal truth — as distinct from moral or personal truth — is what our society revolves around. I read an article in the newspaper several years ago about the voice-stress detectors that are used to see if a job applicant is lying. I was astonished that such things existed and are used. I got some sales literature and read more articles about them. I just pushed the idea of absolute truth to its bitter end, to the point where it became a personal tragedy.

Sawyer: How did you develop your vision of Toronto at the turn of the next century?

Green: I looked backward 15 years. The world of 1973 had minor but significant differences from our world of today. Back then, I bought an electric typewriter which was regarded as the ultimate achievement in writer’s tools. Today, we have a computerized world. The video tape has revolutionized home entertainment. Now there’s an outlet for them every six blocks. A person from 15 years ago reading today’s Toronto Star would be astonished at the things that are for sale. And yet, our lives haven’t significantly changed. We still worry about and care about our children, our careers. It’s the peripherals to our lives that change. Fifteen years hence there will be similar changes. The Barking Dog might be one such: a sensing device that can correlate information about body functions, voice inflection, and so on and come up with an absolutely correct determination of whether a person is lying or telling the truth. And yet, despite such devices, people will still be worrying about the same things, having the same anxieties, trying to build the same kinds of personal relationships.

Sawyer: Science Fiction gives you a huge canvass: all of space, all of time, all forms of life. Yet you limit your stories almost exclusively to Earth, to human characters, and to the present, the recent past, or the near future. Why choose science fiction as your field and yet not take advantage of its scope?

Green: There hasn’t been a lot of good science fiction. Most of it is just outrageous fairy tales for adults. But I’ve always thought the genre could produce literature. This may sound presumptuous, but I like to think one of the reasons I set myself the task of using this field is so that I can help elevate it to the level of literature. To do that, you can’t divorce it from all the literature around it. So I move very slowly from standard literature, rather than taking a quantum leap and writing about the year 1,000,000. I’m not aiming my fiction at a hard-core science-fiction audience. I’m aiming at a wider audience and to get that wider audience you have to welcome them into the world of the fantastic a little bit more slowly. I don’t regard myself as a science-fiction writer; I regard myself as a writer who gives a fantastic twist to his stories.

Sawyer: You’re a full-time English teacher. Is writing going to replace that as your career?

Green: I don’t see writing as a career, nor as an avocation. I see it as a passion and as a life. I see it as something I have to do because I can do it. I have no idea where it will lead. It’s like being able to play the piano and not playing it. There’s a sense of waste. I have to write these books. It’s not easy to keep both teaching and writing going. I’ve put in many years teaching. I have commitments and a future in it, so I’m not prepared to toss that aside for the wild fantasy of being a writer. But I do try to make time for writing. I have taken four years’ salary spread over five so that I could have a year off to write. If, by wild happenstance, the writing takes off, I may be able to more evenly balance my time between writing and teaching. Teaching, like writing, is a great thing, but to ignore the writing would make me one-dimensional.

Sawyer: You’ve got a short story collection in print as well as your first novel. Which form do you prefer?

Green: The short story is a home I’m comfortable with. If you had read only my short stories, I think you’d probably call me a sensitive writer. A novel has to be more dramatic. You have to take at least three plots and weave them. It’s very much a plotting job. I think one form is a break from the other. You have to do novels, you have to stretch your wings, try to reach a large audience. But I will go back to short stories.

Sawyer: Barking Dogs started out as a short story in the May 1984 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. Why did you decide to expand it into a novel?

Green: I wanted to write a novel. It’s the greatest commitment a writer can make, representing the greatest amount of pain, the greatest fear. But I needed a place to start. Somebody said to me, `I put down your short story and I was just getting into it. I wanted more.’ I realized I had more to say. Doing a novel version is a completely different experience, both esthetically and from a marketing point of view. Both the short story and the book have lives of their own and may find wholly different audiences.

Sawyer: Your short story collection was published in Canada. Your novels are published in the United States. What are the differences between the two marketplaces?

Green: If you want to sell in this genre, you have to go for the U.S. market — it’s ten times the size. To be published means to be read, to be appreciated, to be considered. You need numbers to do that. Something that’s just published in Canada never seems to make it. My short story collection is a case in point. Pottersfield Press produced a book that was lovely in conception, in achievement, in physical product. It’s getting excellent reviews [see Books in Canada, June-July 1987, p. 18]. But that book is history already. The publisher doesn’t have the money to promote it and there’s just not enough readership here to keep it alive. If The Woman Who Is the Midnight Wind had been published as a mass-market paperback south of the border, I’d have 60,000 readers instead of 1,000.

Sawyer: Barking Dogs is set entirely in Toronto; the main character in Children of the Rainbow is Canadian; there are no American characters in either book. Despite your interest in the numbers of readers in the States, aren’t you rebelling against that country?

Green: Rebellion is a strong word, but it is a conscious decision. I may lose as a result of it. I’d like to think there’s a place for Canadians on the world stage. I’ve been pleasantly surprised to find no negative reaction to the Canadian settings and characters from my U.S. publishers. Canada is an interesting place. The rest of the world thinks so, even if Canadians themselves don’t.

Toronto writer Robert J. Sawyer is The Canadian Encyclopedia‘s authority on Science Fiction.

Robert J. Sawyer online:

Website • Facebook • Twitter • Email