MORE SPOILERS — BIG ONES — YOU’VE BEEN WARNED!

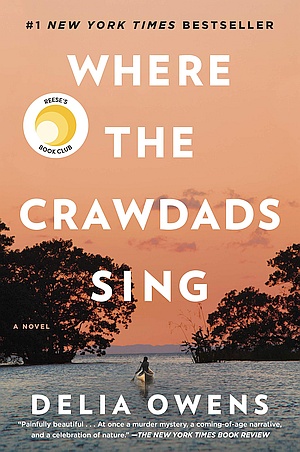

Yesterday, in PART ONE of this discussion, I wrote about some of my problems with Delia Owens’s debut novel Where The Crawdads Sing. As I said then and I reiterate now, I did enjoy the book, and certainly don’t want to take away from anyone else’s admiration of it. It was, after all, the #1 bestselling book — both fiction and nonfiction — in the US in 2019; this novel clearly deeply touched a lot of people.

Again, though, I come at every reading experience cursed by being a writer myself. Yes, there are times when that perspective gives me joy perhaps beyond what a non-writer reader might get from a book: an appreciation of a technical achievement that is so apparently effortless on the page that most readers wouldn’t even notice what had been done. But it can also make stand out things that I, and most of my colleagues, would have done differently, and, we like to think, better.

The same is true, of course, for professional filmmakers, painters, athletes, musicians, dancers, and more: a trained eye or ear is a mixed blessing when it comes to enjoying works in your own field.

Indeed, that’s why my own field of science fiction has two major awards — the Hugo, so the readers can give an attaboy or an attagirl to works they liked, and the Nebula, so other pros can admire the craft. Although there have been times when both awards have gone to the same novel, more often they go to completely different works. There’s no doubt that Where The Crawdads Sing has taken the mainstream equivalent of the Hugo — the people’s choice award — but I doubt it’s likely to win major accolades from other writers.

Anyway, before I dive into the principal issue I wish to discuss, I want to say a bit more about Kya, the main character. Yesterday, I mentioned how much of an absolute genius she must be — world-class marine biologist based on reading a handful of books (plus, of course, years of field observation) and a painter of works so brilliant they’re collected into volume after volume, despite never having had a single art lesson.

But, on top of that, Kya is also drop-dead gorgeous. It’s said repeatedly in the novel: boys lose their heads over her (Chase damn near literally).

Now, yes, there were many a natural beauty in history, but we’re talking about someone who is gorgeous in the eyes of American teenagers and men in the era of blonde bombshells Marilyn Monroe and Tuesday Weld, and I’m not wholly convinced that a woman who has grown up in a swamp, who has never had a haircut except one she did herself, never had dental care, and never been to a doctor, would pass muster with that crowd. And, yes, I’d say precisely the same thing if Kya was a man; I’d very much be surprised to see all the women in Barkley Cove swooning over someone they called Marsh Boy.

So, we’ve got a genius-level intellect, a brilliant artist, a gorgeous face and amazing figure, and someone who, in the end, gets away with killing the man who had mistreated her. You can see why so many people wanted to be that character — why this book has resonated with so many readers.

But, in fact, Kya precisely fits the definition of a Mary Sue. Per Wikipedia: “Mary Sue is a generic name for any fictional character who is so competent or perfect that this appears absurd, even in the context of the fictional setting. Mary Sues are often an author’s self-insertion or wish fulfillment.”

Of course, some might object that my own creation, Caitlin Decter in the WWW trilogy (Wake, Watch, and Wonder), is both intellectually gifted and physically attractive, so who am I to talk?

Indeed, yes, Caitlin has those attributes, and I won’t defend at length, except to say that her attractiveness serves a thematic point. Unlike Kya — who falls for Chase, the stereotypical high-school quarterback, who, in turn, wants her only because she is gorgeous and unrestrained in lovemaking — Caitlin’s attractiveness, which she is utterly indifferent to herself, having been blind almost her whole life, leads her to pick a worthy partner in the kind and supportive, but outwardly unattractive, Matt.

I was doing something thematic about inner lives, in a trilogy in which the central conceit is the exploration of an entity, Webmind, who has nothing but an inner life and no physicality at all.

Anyway, on to narrative voice.

The choice of how you’ll tell a story is one beginning writers rarely give much thought to, but it’s crucial to the impact you’re going to have on readers. Whose story is it? Does that mean that person should be the viewpoint character? Maybe … but maybe not: see Ishmael in Moby-Dick, Dr. Watson in all of Sherlock Holmes, and so on.

And in what voice shall the tale be recounted? In first-person (I did this); in second person (you didn’t do that!); or in third-person (he / she / they did something)?

For Crawdads, Delia Owens apparently made the most-common choice, which is that the main character is also the principal viewpoint character, and the story is told in third-person (Kya did this).

But there’s more to a choice of narrative voice than just that. Third-person narration can be either limited (you are privy to the inner thoughts of only the viewpoint character) or omniscient (you get to hear the thoughts of all the characters in a scene).

The power of limited third-person (or first-person) is that the reader becomes the viewpoint character in a psychological sense: that’s precisely what we mean when we say the reader identifies with the character: by seeing the world through his or her eyes only, by knowing his or her thoughts only, you, the reader, become the main character, and the novel becomes your story. It’s the principal appeal of modern fiction, and it’s the one thing TV and movies can’t effectively emulate. In those latter media, you are a spectator, watching what happens to the hero, but in a novel, you are the hero, mind-melding with him, her, or them.

Now, there are other possible versions of third person, and a good writer might employ them for specific reasons.

As I’ve often said, The Maltese Falcon by Dashiell Hammett is one of my favorite novels — and that’s not just because of the memorable characters, snappy dialog, and clever plot. I also love it because Hammett pulled off a technical tour de force. Although detective Sam Spade is the viewpoint character, inasmuch as we mostly follow him from scene to scene, we never enter his head; we never are privy to his thoughts.

Nor do we enter anyone else’s head. All we hear are the characters spoken words and all we see is their body language, which Hammett describes in almost forensic detail: every quirking of a mouth, lifting of an eyebrow, glance to one side, and more. He never tells us what people are thinking, but leaves us to deduce it, if we can, from posture and facial expressions.

Why did Hammett do that? Simple: everybody in The Maltese Falcon has a hidden agenda, everyone is lying to everyone else, and the reader is left guessing right up until the end about what’s actually going on. If we were privy to Sam Spade’s thoughts, the whole novel would fall apart: we’d know what he was up to before the end. And there’s no natural sidekick (no Dr. Watson) with him in most scenes whose head we can enter either. And so Hammett devised a narrative technique that let him tell his mystery tale without ever once violating his own rules and thereby always playing fair with the reader.

Well, Delia Owens faced a similar challenge in constructing Where the Crawdads Sing, and, in my opinion, from a novelist’s perspective, her answer is a cheat.

Yes, she does give us pale imitations of Hammett’s dispassionate external appraisal by the narrator:

Kya returned to the porch steps later and waited for a long time, but, as she looked to the end of the lane, she never cried. Her face was still, her lips a simple thin line under searching eyes.

But sometimes Owens does want us to know specifically what Kya is thinking, and so we bore into Kya’s skull and are indeed able to access her stream of thought (in what’s called limited third-person point of view, the standard mode of most modern fiction):

Kya touched the words as if they were a message, as though Ma had underlined them specifically so her daughter would read them someday by this dim kerosene flame and understand. It wasn’t much, not a handwritten note tucked in the back of a sock drawer, but it was something. She sensed that the words clinched a powerful meaning, but she couldn’t shake it free. If she ever became a poet, she’d make the message clear.

So, sometimes we can hear her thoughts and sometimes we can’t. And when we can’t but Owens still wants us to know what Kya is thinking, she has Kya talk out loud to herself, which is clumsy as hell. For instance, upon finding a feather Tate has left for her, Kya speaks her inner monologue even though she’s all by herself:

“How’d it get stuck straight up in the stump?” Whispering, Kya looked around. “That boy must’ve put it here. He could be watchin’ me right now.”

But then Owens decides to essentially have no rules at all about what we can and cannot know, except as it serves her plot. For instance, suddenly, in the same scene, we go from watching Kya without knowing what Kya is really thinking to being right inside the head of Sarah Singletary, the grocery-store cashier:

Sarah glanced at Kya and remembered the little girl coming barefoot into the market for so many years. No one would ever know, but before Kya could count, Sarah had given the child extra change — money she had to take from her own purse to balance the register. Of course, Kya was dealing with small sums to start with, so Sarah contributed only nickels and dimes, but it must have helped.

Now, why does this bother me so much? Simple: the whole plot of the story depends on the reader not knowing what Kya knows, and not being privy to Kya’s thoughts on crucial matters. All the time Kya is sitting in jail, and all during her trial, we don’t get to know what Kya is thinking because, of course, any honest account of it would be that she was thinking things such as:

- Yeah, maybe they’ll send me to the electric chair, but I’m still glad I killed Chase.

- Ooops! I didn’t do as good a job of covering my tracks as I thought.

- Hah, fooled that witness! My disguise was good!

And, once you allow head-hopping (suddenly reading the minds of characters other than the original viewpoint character in a scene), you’re cheating if you don’t do it when the other characters in a scene have secrets. Chase must have been thinking all the time he was with Kya that if he kept falsely promising to marry her, she’d continue to provide wild sex. But if we’d known that, there goes the plot.

The artform Delia Owens tackled is a tricky one: the subgenre of mystery fiction in which either the detective is actually the killer or the presumed-to-be-innocent accused is. It’s very hard to play fair with the reader under such circumstances; it requires a lot of narrative finesse to pull off. And, despite all of its many other virtues, I simply found that finesse lacking in Where the Crawdads Sing.

For those who are curious, I talk more about the writer’s craft as related to point of view in this column:

Point of View

I’d orginally posted the above, as well as yesterday’s post, which was also about Where the Crawdads Sing, on my Facebook wall, and that led to this question from a reader there and my answer:

This is very insightful, thank you Robert :)

I feel I’m missing something important, though. Why do you regard the selective disclosure of internal information (thoughts/motivations) as worthy of a different treatment to the selective disclosure of external information (spoken words, body language, environment)? Isn’t selective disclosure the prime prerogative of the author?

As far as I can determine (and please forgive me if this seems reductive or uncharitable to someone at your level of his craft!), one might simplify a description of fiction to something like “the author tells you what they want you to know about a world they have imagined, in precisely the order they want you to know it.”

Based on this description I wouldn’t call Owens’ selective head-hopping “cheating” any more than I’d call withheld information in your novel Red Planet Blues “cheating,” because there couldn’t be a story without it. That to me suggests I haven’t understood why Owens’ approach is a faux pas.

Thanks!

My reply:

Well, in one sense, you’re right: the author can do whatever he or she pleases; that’s his or her prerogative.

But the reader is also entitled to accept or reject what the author does; that’s the reader’s prerogative. And when the author is clumsy, we have a term for it: we say the author has been manipulative. And Delia Owens was, in my view.

And speaking of prerogatives, what the character says vs. what the character thinks is actually the character’s prerogative (yes, I know, the author has created the character, but bear with me): if I see that lousy son-of-a-bitch I just can’t stand coming toward me — well, that’s what I’m going to think; I, the character named Rob, has no volition about what thoughts occur to me. But what I say to that person as he comes up to me — forced friendliness, open hostility, or nothing at all — is something I do get to choose.

What Owens did was show us the characters’ thoughts when it suited her and withheld them from us when it suited her: that’s both manipulation and lazy writing. In most other books, you either are or are not in the main character’s head; you aren’t pulled in and out at the convenience of the author.

It’s akin to the narrative rule that the description must include everything significant that a cursory examination of the scene by the viewpoint character would reveal. It’s fair to say this:

I opened the door, saw that there was a lion in the room but went in anyway, trusting that the animal wouldn’t kill me.

It’s unfair to say:

I opened the door, walked into the room, sat in the easy chair, picked up a magazine, did the crossword at the back, and then the lion — oh, hey, did I mention there was a lion in the room? — bit my foot off.

To your point about Red Planet Blues, well, I’m not going to provide spoilers for my own novel here (this thread clearly identified it as having spoilers for Crawdads only, and I prefer to limit it to that), but in my novel (which is told in first-person narration) you are 100% privy to Alex Lomax’s thoughts: you’re in his head and you hear exactly what his stream of consciousness would naturally be at each point in the novel; at no point does he conveniently become a black box impenetrable to the reader.

Now, the fact that you likely misinterpreted what he thought is me being artful — but it’s also natural, as I hope this slightly over-the-top example will demonstrate. If I’m feeling nostalgic, I might think something along these lines:

I miss my hometown.

That’s a legitimate transcription of my thought, precisely as I might think it. Now, what would not be natural would be if I’d purported to transcribe my thought thusly:

I miss my hometown, which is Ottawa, and although many people think where I live now — Toronto — is Canada’s capital, that’s not true; it’s just the provincial capital. Ottawa, formerly known as Bytown, is the national capital — although, interestingly, both Ottawa and Toronto are in the same province, the one called Ontario.

You might argue that, hey, the first version was withholding information that the second one conveys, but only the first one is what anyone would actually think in the moment, and Alex isn’t hiding anything in Red Planet Blues; you’re just guessing wrong about what he’s referring to when you read his thoughts: every time Alex thinks of the thing you’re wondering about in Red Planet Blues, he thinks about it precisely as he naturally would, and the thought is honesty and accurately relayed in the text.

Also, the plot of my novel does not in any way hinge on the thing I allowed the reader to misconstrue. It only affects how the reader might feel about Alex after he or she turns the last page.

But in Crawdads, the plot — the entire mystery — depends on us thinking we’re privy to Kya’s inner life only to discover that we’ve been lied to about that all along.

And that, my friend, in my view, is cheating.

GO BACK TO PART ONE

Robert J. Sawyer online:

Website • Patreon • Facebook • Twitter • Email

![[Einstein's 70th birthday]](https://sfwriter.com/rogue's-gallery.jpg)

![[Wernher von Braun]](https://sfwriter.com/von-braun-in-cast.jpg)

![[Robyn Herrington]](http://sfwriter.com/robyn-1.jpg)

![[Robyn Herrington]](http://sfwriter.com/robyn-2.jpg)

.jpg)