After a three-month hiatus, FlashForward, the ABC TV series based on my novel of the same name, returns to television this week. On Tuesday, March 16, 2010, at 10:00 p.m. Eastern and Pacific (9:00 p.m. Central), a one-hour clip show entitled "What Did You See?" (a catch-phrase straight out of my novel) airs (immediately following Lost).

And on Thursday, March 18, at 8:00 p.m. Eastern and Pacific (7:00 p.m. Central), a new two-hour episode, "Revelation Zero," airs -- and we'll be on without repeats or pre-emptions every week after that for ten more weeks.

What follows are some of my thoughts about the show and being involved with it.

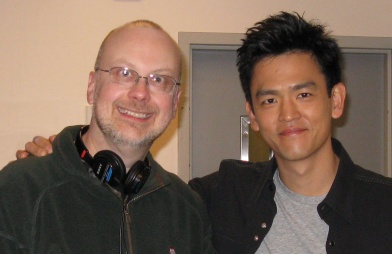

It's a sweltering day in August 2009, and I'm in Los Angeles, at a location shoot for

FlashForward, as we're filming the sixth episode of the TV series based on my novel of the same name.

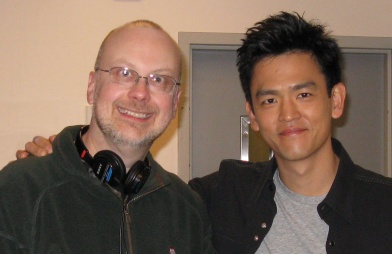

John Cho (pictured with me above), one of our stars, comes up to me to say hello. We haven't seen each other since filming the pilot, back in February 2009, and he's been wanting to ask me a question since then: "What happens to my character?"

He's right to wonder. In our first episode, everyone on Earth blacked out for two minutes and seventeen seconds. Millions died during that time, as people tumbled down staircases, cars smashed into each other, planes crashed as they tried to land, and so on. Those who survived had interlocking visions of what their futures might hold six months down the road.

Except, apparently, for John Cho's character, impetuous FBI agent Demetri Noh. He told the others in the first episode that he'd seen nothing at all -- and, he said, he's terrified that means he'll be dead in just half a year.

The storyline of a guy who has no vision when almost everyone else does is straight out of my novel, so my first thought is to tell John that he should do what fellow series stars Joseph Fiennes (who plays John's partner at the FBI), Sonya Walger, Dominic Monaghan, and Zachary Knighton did: read my book. But instead I decide to immediately put him out of his misery.

I look left and right, to make sure we aren't being overheard, then say, "Well, John, your character is actually lying when he says he didn't see anything. The truth is, six months down the road, Demetri sees himself in a gay bar, and doesn't want to admit that to his macho FBI partner."

John looks skeptical, so I smile and say, "Hey, look, you're the guy playing Sulu now in

Star Trek, right? What was the big reveal about the original Sulu, George Takei? Seemed like a good notion to copy."

Of course, that's not the real answer. The truth is hidden in the

FlashForward writers' room, which is located on the ABC Studios lot just across a small alley from the writers' room for

Lost (from which I hereby deny that we constantly hear anguished screams).

Our room has a giant wall chart divided into twenty-two columns and thirteen rows: one column for each of our first-season episodes, and one row for each character. The actors are forbidden to enter the room, but John's true fate is written there in the appropriate box.

I wish there'd been such a board for my own life. My novel

FlashForward was first published in 1999, and I had real doubts back then about whether my writing career was going to flourish. I'd have loved a glimpse in 1999 of what my own future would hold; it would have saved me a lot of sleepless nights to know that the crazy gamble of trying to be a novelist was going to pay off.

Yes, by the time

FlashForward was published I'd already

won the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America's Nebula Award for Best Novel of the Year, but I'd yet to hit any major bestsellers list (that came the following year, with a book called

Calculating God). And the biggest prize in science fiction, the Hugo, had eluded my grasp, despite several nominations by that point (I did finally win it in 2003, for my novel

Hominids).

But I'm not sure that I'd have believed this future had I seen it.

FlashForward isn't just any TV show; rather, it's the hottest new dramatic program of the year in the US, and it's already sold to a staggering 100 territories worldwide. The juggernaut that

FlashForward has become is, frankly, overwhelming.

Working on a big-time TV series (I'm writing episode 19, and serving as consultant on all of them) is new for me. Likewise, it was the challenge of doing something different, I'm sure, that attracted big-name actors to this project. John Cho is known for comedic roles in movies (he's Harold in the

Harold & Kumar films), but in

FlashForward he's getting to show the world what an incredibly fine dramatic actor he is.

Indeed, all our actors are playing very tough material. I have a tiny cameo in the pilot as "Man on Cell Phone" behind Sonya Walger while she's talking about the worldwide disaster with Joseph Fiennes's character on her own mobile; Sonya was so intense during our little scene together that director David S. Goyer had to keep reminding her to blink.

Joseph Fiennes is known for his Shakespearian work, including playing the bard himself in

Shakespeare in Love. During the filming of the pilot, I loved watching Joe bop between doing a tough-guy American voice for his

FlashForward character of Mark Benford, and then, as soon as director Goyer called "Cut!," immediately switching to a foppish British voice and reciting lines from

Cyrano de Bergerac, as he rehearsed for his role in Trevor Nunn's production of that play this past summer. Joe put Sally Field's back-and-forth transformations in

Sybil to shame.

As I look back on it, I'm still stunned that this particular future for me has come to pass. It's been a long road getting to where the show is now. In Hollywood, everything is about who you know -- and my agent there, Vince Gerardis, has long known producer Jessika Borsiczky. As soon as the

FlashForward novel was published, Vince gave Jessika a copy, and she got her friend (and later husband) David S. Goyer to read it. They immediately agreed that they wanted to adapt my novel for film.

Later, when David teamed up with Brannon Braga of

Star Trek fame to work on a 2005 TV series called

Threshold, Brannon -- who was independently a fan of my books -- said that

FlashForward would be even better as a TV show, and together David and Brannon wrote the pilot script.

My mother taught statistics at the University of Toronto; all my life, I've been calculating odds, and never figured I'd beat them. Maybe one novel in a hundred has its film or TV rights optioned (most of mine have at one point or another), but then only one in a thousand of those ever actually gets made. I never expected any of mine to be filmed, and I certainly never expected anything on this scale.

When we got the go-ahead to make the pilot -- and at ABC, no less! -- I was gob-smacked; I felt like I'd won the lottery. (And, to my delight, David Goyer told my hometown paper,

The Toronto Star, that "I felt like I'd won the lottery of television writers" when he read my novel.)

When the series was picked up by ABC for its initial 13-episode order (now extended to 22), David said, "This will change your life." And it has -- and not just because the darn phone won't stop ringing. Still, it's strange knowing, at 49, that when my obituary does eventually run, the fact that

FlashForward was adapted into a TV series will be the thing I'm most noted for.

Looking back on it, it's amazing from how small a seed a global phenomenon can spring.

FlashForward grew out of my high-school reunion at which everyone -- and I mean everyone -- said the same thing: if I'd only known back then what I know now, my life would be better. They were sure they'd have avoided marrying that jerk, taking that dead-end job, or making that bad investment.

Well, as a science-fiction writer, I couldn't hear that without wanting to explore it with a thought experiment: what if people really did know their futures? Would attempts to alter that future actually work?

(You don't need a $100-million TV series to test that proposition, though; just ask yourself, whether, with all your good intentions and conscious will, you've managed to keep your New Year's resolutions.)

In my novel, I make the analogy that time is like a movie: the frame that's illuminated is "now," and the stuff before it is what you've already seen. But what's to come later is already established, as well; it just hasn't been revealed yet.

Well, for

FlashForward, I

have seen the future; I know what tomorrow holds. But I'm not telling. You're going to have to watch -- and, I hope, read! -- to see how it all unfolds.

Robert J. Sawyer online:

Website • Facebook • Twitter • Newsgroup • Email

Labels: Flashforward