The Adolescence of P-1

by Rob - July 15th, 2009.Filed under: Wake.

In the summer of 1980, Carolyn and I moved to Waterloo, Ontario, for four months, to share an apartment with our great friends Lynn Conway and Fraser Gunn. (Their previous roommates, students at the University of Waterloo, had moved out at the end of the academic year.)

That summer, I did a few things that had a profound impact on my career.

First, I outlined my very first novel, End of an Era.

Second, because he was to be Guest of Honour that summer at the very first Ad Astra — Toronto’s now-venerable science-fiction convention — I read James P. Hogan‘s Inherit the Stars, which, to this day, is still one of my favourite science-fiction novels (and doubtless an influence on the watch-the-science-puzzles-go-snick-snick-snick aspects of End of an Era).

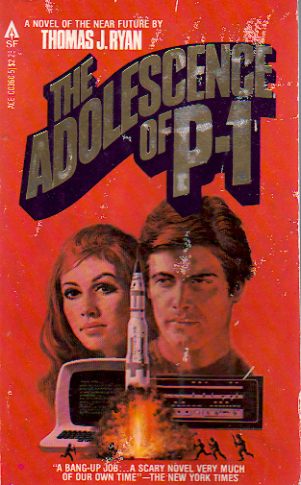

And third, at Fraser’s suggestion, I read The Adolescence of P-1, by Thomas J. Ryan — because it was a science-fiction novel set in part in Waterloo.

Flashforward (heh heh) 29 years, and I find myself in Boston at Readercon 20, and my friend Judith Klein-Dial has a mass-market paperback of The Adolescence of P-1 for sale for a buck at her table. I own a hardcover of P-1, but it’s up in Toronto, and I need something to read on the flight home, so I make peace with my usual compunctions about buying used books, purchase the copy, and start reading it.

Like my current novel WWW: Wake, Ryan’s The Adolescence of P-1 could easily pass for mainstream: it’s set in the then-present of 1977 (the book was first published that year).

And, like my Wake, it was published (in mass-market at least) by Ace (the hardcover had been from Macmillan, and the most-recent reprint is from Baen).

And, like my Wake, as I said, it’s set in part in Waterloo, Ontario.

And, most of all, like my Wake, it deals with the emergence of consciousness in networked computers (in P-1, networked by phone lines; in Wake, of course, via the Internet and the supervening World Wide Web).

Now, let me say this: I loved The Adolescence of P-1 as a 20-year-old, and I still find a lot to like about it as a 49-year-old. But it is a classic example of what actually compelled me to write Wake in the first place. As I’ve said in interviews about my book, previous SF treatments of the ramping up of intelligence by computers either have the big event happening off stage (as in Neuromancer) or simply skip over the hard bits, as in, well, The Adolescence of P-1:

The System had an idea.

An idea?

Sounds absurd out of context. A computer program with an idea. This, of course, was the computer program that snookered John Burke and the entire Pi Delta/Pentagon security arrangement — bypassed, in fact, every security system on every computer in the US. This was also the program that daily read the Los Angeles Times, the Washington Post and the New York Times. All those publications were computer typeset and quite available for The System’s perusal.

Computer typesetting also made available Howl, Tales of Power, The Idiot, Little Dorrit, The History of Pendinnis, Summerhill, Amerika, Stranger in a Strange Land, the complete works of Shakespeare, Conan Doyle, Twain, Faulkner, and Wodehouse. The System might have been called an avid reader.

[Ace August 1979 mass-market paperback, page 109]

Hello? How does this AI read anything? How does it comprehend even a single word of English?

As SF Site observed in its very kind review of Wake:

Now, the idea of a digital intelligence forming online is not a new one, by any means. But I daresay most of the people tackling such a concept automatically assumed, as I always did, that such a being would not only have access to the shared data of the Internet, but the conceptual groundings needed to understand it.

And that’s where Robert J. Sawyer turns this into such a fascinating, satisfying piece. In a deliberate parallel to the story of Helen Keller, he tackles the need for building a common base of understanding, before unleashing an education creation upon the Web’s vast storehouse of knowledge.

He incorporates the myriad resources available online, including Livejournal, Wikipedia, Google, Project Gutenberg, WordNet, and perhaps the most interesting site of all, Cyc, a real site aimed at codifying knowledge so that anyone, including emerging artificial intelligences, might understand.

He ties in Internet topography and offbeat musicians, primate signing and Chinese hackers, and creates a wholly believable set of circumstances spinning out of a world we can as good as reach out to touch. Sawyer has delivered another excellent tale.

So, as my character of Caitlin would say, “Go me!” :)

Or, if I may be so bold, as Stanley Schmidt, the editor of Analog Science Fiction and Fact (where Wake first appeared as a four-part serial), observed:

Robert J. Sawyer has a way of taking familiar ideas, looking at them from new angles and in greater depth than almost anybody before him, and tying them together to create extraordinarily fresh and thought-provoking stories.

It’s often said that science fiction is a literature in dialogue with itself (the classic example is Robert A. Heinlein‘s Starship Troopers as opening remark and Joe Haldeman‘s The Forever War as response).

A number of reviewers have mentioned that Wake is clearly in dialogue with William Gibson‘s Neuromancer (“If books were movies, I’d suggest this [Wake] on a double bill with Neuromancer” — SFRevu), but it should be noted that it’s also a response to Arthur C. Clarke‘s “Dial F for Frankenstein”, D.F. Jones‘s Colossus (filmed as The Forbin Project), David Gerrold‘s When HARLIE was One, and, most certainly, to Thomas J. Ryan‘s seminal The Adolescence of P-1.

And if I have, in any way, seen a little further than those who went before me, it is, as always, because I stand on the shoulders of giants.

Visit The Robert J. Sawyer Web Site

and WakeWatchWonder.com