30th anniversary of my involvement with Vision TV

by Rob - October 12th, 2013.Filed under: Atheism, Milestones, Nonfiction.

After my keynote address at Science Fiction: The Interdisciplinary Genre, the academic conference held in my honour in September 2013 at McMaster University, I was asked by an audience member about where my interest in, and sympathetic treatment of, religion — which is clearly evident in many of my works, including Calculating God and Hominids — came from.

I replied that I’d spent my teenage years a typical arrogant atheist, thinking that those benighted fools who believed in gods or an afterlife clearly weren’t intelligent or well-read. But thirty years ago today, on Wednesday, October 12, 1983, when I was 23, I began a job — the first really big assignment of my nascent freelance-writing career — that changed that perception.

I’d graduated in April 1982 with a bachelor’s degree in Radio and Television Arts from Toronto’s Ryerson Polytechnical Institute, and had spent the 1982-1983 academic year working at Ryerson as an instructor/demonstrator for TV studio production techniques — and, by that point, I’d already published some fiction and a few articles.

At the beginning of October 1983, Rev. Des McCalmont, the United Church of Canada’s head of TV production, called up his friend Ryerson professor Syd Perlmutter. Des was looking for a recent grad who was up on all the ins and outs of Canadian broadcasting policy to write portions of and supporting materials for an interfaith TV license application. Syd recommended me, and I got the freelance contract (although it was for full-time work).

I moved into an an office at the United Church’s Berkeley Studio, becoming the fifth member (and only full-timer) of The Rosewell Group, a consultancy specifically created to spearhead this license applicaton. The Rosewell Group consisted of Des McCalmont, documentary filmmaker Peter Flemington, lawyer Douglas Barrett, Rev. David MacDonald, who was formerly Canada’s Secretary of State and Minister of Communications — and now me.

I was was with Rosewell for for nine months (moving on at the end of June 1984 to pursue my freelance-writing career), although I continued to do freelance consulting for them for a few years thereafter.

During those nine months, I met and worked closely with people from a wide range of faith groups, and discovered that many, indeed most, were bright, questioning, thoughtful individuals; that experience changed my own perceptions enormously. I remain an atheist, but I learned to respect and appreciate those who have a different perspective.

As a freelance writer, by 1984 I’d become a regular contributor to Broadcaster, Canada’s monthly trade journal for the TV and radio industries, and in its August 1984 issue, editor Barbara Moes ran the following 1,800-word article by me that described the project we at The Rosewell Group had been working on: the creation of a national multifaith cable television service, which at that point we were calling CIN, the Canadian Interfaith Network.

The channel eventually rebranded itself as Vision TV, and finally went on the air on September 1, 1988, four years after this article appeared.

Although Peter Flemington served as Vision’s head of programming and development until 2000, I’m the only member of The Rosewell Group still involved with the service we set out to create lo those three decades ago: I host the skeptical TV series Supernatural Investigator for Vision TV (“World-class. Supernatural Investigator is Unsolved Mysteries for brainiacs.” — Victoria Times Colonist).

I’m providing the following article (1) in commemoration of the 30th anniversary of me becoming involved with Vision TV, (2) as an important part of the woefully underdocumented history of how Vision TV came to be, and (3) as a sample of my work from the 1980s for those fans of my science-fiction writing who are curious about the kind of articles I wrote during my previous career as a freelance writer (for another sample, also on a religious theme, see this 1985 piece, which I was hired for because of my work with Rosewell: “My Day with the Jesuit Brothers”).

NOTES:

Converters: set-top tuner devices that used to be needed to access cable-TV channels

CRTC: the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission, Canada’s federal broadcast regulator; the Canadian countepart of the American FCC

Charles Templeton (1915-2001): at the time this article came out, one of Canada’s best-known broadcasters and journalists — and, in the 1940s and 1950s, an evangelist

“Preaching to the Converters”

by Robert J. Sawyer

from Broadcaster

August 1984

“It was the CRTC who asked us to do this by issuing the Call. For them to turn around now and say ‘you’re not really serious about this’ would be a major slap in the face to Canada’s religions.”

The speaker is the Honourable David MacDonald, Minister of Communication in Joe Clark’s 1979 government.

Controversy bubbles around MacDonald’s proposed Canadian Interfaith Network. Even its nickname — CIN with a soft “C” — sparks debate. Many simply don’t like the idea of religious television. Canon Duncan Abraham of the Anglican Diocese of Toronto cites American “put-your-hands-on-the-set-and-be-cured” programs. “They’re a lot of garbage,” he says.

But The Rosewell Group — MacDonald’s R&D team — has something different in mind. They’re planning shows like CBC’s Man Alive, which attracts a million viewers each week. “It will be an alternative, values-based programming service,” according to their publications.

Rosewell was commissioned by Interchurch Communication to respond to the CRTC’s June 2, 1983, Call for Licence Applications to operate a satellite-to-cable religious programming service. Interchurch is a media committee for the six largest Christian denominations.

For months it appeared that Crossroads Christian Communications, Inc., would file a separate application (they’d previously been denied a strictly-Christian licence). They bought C-Channel’s satellite uplink facility from the receiver for the bargain price of $1 million.

In a dramatic move, Rev. David Mainse, TV evangelist and Crossroads president, appeared at CIN’s founding assembly on April 1st and threw his corporation’s support — and the C-Channel equipment — behind the interfaith application.

It surprised a lot of people, including Charles Templeton, himself a former evangelist. “Jesus wasn’t prepared to share a pulpit — even an electronic pulpit — with someone of another belief. It seems out-of-character for a fundamental conservative Christian to agree to be only one voice of many.”

Indeed, there are many voices involved. When the application was filed on May 1st, MacDonald’s team had signed up fifteen groups besides Crossroads: Anglican, Baptist, Buddhist, Christian Reformed, Greek Orthodox, Hindu, three kinds of Lutheran, Muslim, Salvation Army, Sikh, Unitarian, United, and Zoroastrian. Together, they represent over a third of all Canadians. But how many will tune in to the religious network? Many faith groups already produce shows for cable community-access channels. Duncan Abraham notes “it’s only a small percentage of our people who watch those.”

Rosewell’s Rev. Des McCalmont thinks “there’s a damn good reason” why these shows have tiny audiences. “They’re boring. The community channel looks like it’s being run on penlight batteries. Our stuff will look top-notch.”

The Rosewell Group in February 1984 (click for larger version). Back: Doug Barrett, Des McCalmont, Peter Flemington, Hon. David MacDonald. Front: Robert J. Sawyer, Maureen Levitt (who joined the group that year)

But others share Abraham’s concern. Charles Templeton predicts “the audience for this will be miniscule. It will, in effect, be a religious ghetto.” Paul Morton, President of Global Television, has “great reservations about all the supplementary channels. The Canadian market is so small that I really question whether any of them will have a meaningful audience.”

David Balcon, formerly senior researcher for the CRTC and now a partner in Oursons Consulting of Edmonton, did a 100-page $15,000 study for Rosewell. He feels CIN’s proposed nightly good-news-and-public-affairs show will attract a core audience of a quarter-million Canadians.

“It was decided that the network would not undertake any other regular production,” except the news program, says Balcon. “Shows would be farmed out to, or done in association with, independent producers.”

CIN will really be two different programming services, each with a distinctive logo. One’s called Mosaic, which will consist of denominational productions. Upon joining, each group promises to provide at least one hour’s worth of programming a month.

The other service is Cornerstone, general-interest religious programming, dealing with issues of the human spirit. No one perspective will dominate. Rather, the programming will be a value-based alternative to what’s currently on the air. In the words of the Rosewell Report newsletter, Cornerstone is intended “to appeal to those of all religions and those of no particular religion.”

But some see a problem with Cornerstone. Canon Abraham notes: “David Mainse says homosexuality is a great sin. The United Church has brought in a report that recommends the ordination of homosexual clergy. How can they live together comfortably without the programming ending up being wishy-washy? It’ll be the lowest common denominator.”

McCalmont is confident that the network’s board of directors — twenty men and women culled from the participating faiths — will be able to work it out.

There are other concerns about program content. “In the early years, they’re prepared to sell time to the American evangelists,” says Abraham. The Balcon model does require up to 40% of the Mosaic airtime in year one to be sold to existing television ministries. “We question whether we want be in bed with them.”

McCalmont isn’t worried. “Faith groups are happy to go on the air now alongside Preparation H commercials. Besides, there’s a lot of good stuff in the States. It’s not all Rex Humbard. If there are American evangelists on the network, they will be subject to the Code of Ethics.” That code says in part that no one asking for money will be allowed to be “unduly alarmist” or “predict any negative divine consequence as a result of not responding.”

Whatever the content, television is a big-bucks industry. Balcon had originally proposed a $30-million budget by year five. Because of negative reaction from some faith groups, that’s been radically reduced. CIN lawyer Douglas Barrett and Scarborough cable president Geoff Conway have devised what they call “Optimum” and “Conservative” scenarios for the network. The optimum scenario would eat up $19 million in operating costs during the first year and $23 million by year five. The conservative scenario calls for $13 million the first year rising to just $15 million by the fifth.

Cut from Balcon’s report were the branch offices in Vancouver, Winnipeg, Montreal, and Halifax. “I feel strongly that they need those regional offices,” says Balcon. Roman Catholic Father Jack Bastigal, who lives in Calgary, agrees: “We want a piece of the action.”

The cutting of the Montreal office is a particularly sensitive issue. At the network’s founding assembly, Roman Catholic observer Guy Marchessault declared the model was “not at all satisfactory for French Canadians. It’s impossible to convince the French public that you will make quality French-language programs in Toronto.”

Bastigal echoes that sentiment. “The French side of the Catholic Church will only be happy if there are some definite commitments from CIN that French programming will be available almost immediately. They won’t stand for being treated as second best.”

David MacDonald is sensitive to the Francophones’ concerns. “We’re aware that there’s still a good deal to be developed to make this a fully national application truly reflective of Canada’s linguistic and cultural realities.”

CIN will be delivered to cable systems via two Anik-C satellite transponders. Balcon’s report suggested that more French programming be included on the transponder that’s serving Quebec.

CIN is gearing up for its public hearings, scheduled for November [1984]. One issue that’s sure to be raised is the lack of commitment by the Roman Catholic Church, representing 11.2 million Canadians, and the Canadian Jewish Congress, 300,000 strong. “Will the thing be viewed as an interfaith network if the Romans and the Jews aren’t part of the picture?” asks Duncan Abraham.

Charles Templeton is blunt. “Quite candidly, I think they’re doing the right thing” by not participating. “After the first blush of debut, they will be virtually without an audience.”

Father Barry Jones, the Catholic representative to Interchurch Communication, doubts the Catholics will come on board soon. “Given that the decision comes before the Bishops following an historic, costly papal visit, it’s unlikely that they will then turn to the multimillion-dollar unproven Canadian Interfaith Network with a resounding yes.”

“We’ve made it very clear that in whatever way possible we welcome their maximum consultation and participation,” says David MacDonald. To this end, CIN has opened three observer seats on its Board of Directors: one each for a French Catholic, an English Catholic, and a Jew.

“We wish to make it clear to the CRTC that our application has attempted — and in large measure succeeded — to involve all the main and many of the smaller faith communities,” says MacDonald.

It seems apparent, however, that the Commission intended to receive applications for a specialty, viewer-discretionary channel. CIN wants mandatory carriage on basic cable or on a freely available, unscrambled spot on the converter. “We’re a mainstream service,” says MacDonald, “speaking to all Canadians.”

David Balcon agrees: “It’s ridiculous to say that people who buy General Foods products are a more meaningful constituency than those interested in issues of the human spirit. If CIN can pass the quality test, it should be entitled to the same priority carriage as other Canadian networks. The Commission will have to realize that satellite-to-cable can be as important a means of carriage as over-the-air.”

The regulator will also give close scrutiny to funding. “The question on everybody’s mind,” according to Balcon, “is André Bureau’s approach to financing: the need to have a banker’s letter in hand when you sit down in front of the Commission. That’s the only real obstacle to granting a licence.”

Rosewell has proposed a $28-million national fundraising campaign to get the network up and running. Half of the funds collected would go to finance the service; the rest would be split amongst the participating faith groups as seed money for their programming. McCalmont thinks the money is there; Abraham doesn’t see “the same level of support for this project” as for other church funding drives.

David MacDonald refuses to start seeking money from the public before receiving a licence. “It’s a question of being realistic. We’re willing to embark on this fundraising campaign, but only if it has a purpose. And it won’t have a purpose unless the Commission guarantees to grant a licence if we are successful.”

The cash flow for the network depends on sales of airtime. The rate card calls for $12,000 per prime-time hour for member groups, double that for foreign buyers. Crossroads, the producers of 100 Huntley Street, have already expressed a strong interest in buying airtime in bulk. “There are a couple of broadcasters who will be quite panicked,” predicts Balcon. “Global and Multicultural TV [CFMT] in Toronto have a fair dependence on Huntley Street. CIN may syphon off some of that programming.”

Global President Paul Morton says, “We recognize the possibility. By the same token, I think the various religious groups will have to make their own decisions about what kind of distribution they want.” In any event, Global “will not intervene” at the licence hearings.

McCalmont is confident that CIN’s hearings will go well. “It’s an idea whose time has come and it will happen.” The network’s target on-air date is May 1, 1986.

Freelance writer Robert J. Sawyer was one of the authors of CIN’s licence application.

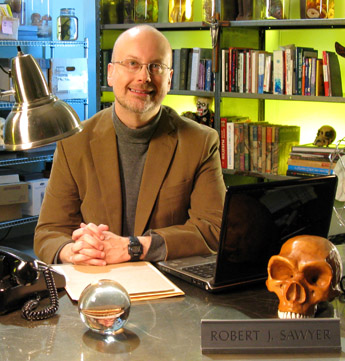

Science-fiction writer Robert J. Sawyer in November 2008 on the set of Vision TV’s Supernatural Investigator, which he hosts.

Robert J. Sawyer online:

Website • Facebook • Twitter • Email